ACCELERATING INDIA’S MANUFACTURING FUTURE

To strengthen India’s innovation capacity and global manufacturing competitiveness, the Ministry of Heavy Industries has launched the Center for Advanced Manufacturing for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (CAMRAS) under its Capital Goods Scheme Phase II, in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, and ARTPARK (AI and Robotics Technology Park).

A sudden surge in imports of robotic and autonomous systems has been observed over the past five years, driven by increased spending on autonomous mobile robots (AMRs), manipulators, collaborative robots, and drones across Manufacturing, Defence, Commercial, and Government sectors. Given the evolving technologies, products, and global trade environment, it has become imperative to promote indigenization and innovation to achieve strategic independence, particularly concerning the security and safety of such products in India. The Ministry of Heavy Industries (MHI), Government of India, has been implementing various schemes to strengthen India’s position in the future of manufacturing.

Building on the Ministry’s earlier successes with the Advanced Manufacturing Centre of Excellence (AMCoE) and Industry 4.0 CEFC programs, CAMRAS (the Center for Advanced Manufacturing for Robotics and Autonomous Systems) focuses on nurturing startups that deliver market-ready technologies (Technology Readiness Levels 7–8) in robotics, automation, and autonomous systems by 2026.

| Building on the Ministry’s earlier successes with AMCoE and Industry 4.0 CEFC programs, CAMRAS focuses on nurturing startups that deliver market-ready technologies (TRL 7–8) in robotics, automation, and autonomous systems by 2026. |

Choosing the FIA Ecosystem Model

A proven ecosystem model is essential to accelerate innovation by bringing together startups, large industries, venture capitalists, academia, and autonomous research institutes in the development of advanced manufacturing technologies. The new Fibonacci Innovation Acceleration (FIA) ecosystem model aims to deliver immediate impact while enabling the creation of differentiated products and technologies over the next decade. Its key objectives are to:

- Rapidly develop products by leveraging existing Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 3 technologies and position them among the best globally over the next five to 10 years.

- Build products and supply chains for a stronger manufacturing economy and achieve strategic independence by 2030.

The following section outlines the strategic technology gaps projected for the next five years and the preparedness required by 2030, keeping the objectives of the CAMRAS program in focus. The CAMRAS program was conceptualized in July 2022, approved as an MHI Accelerator initiative in November 2022, and became operational in January 2023, with completion targeted for March 2026. The MHI had already designed the framework to develop this ecosystem and integrate current and existing manufacturing units into it.

| The success of the program depends on the choice of leaders. Their competencies must range from leadership, behavioral and financial management, program and project management, business management, industry relations, investment/ VC relations, team management, and technology integration. |

Investible Technologies and Business Model Analysis

Artificial intelligence, robotics, autonomous systems, Industry 5.0 solutions, sustainable materials, energy optimization, self-managed products, advanced sensors, and assistive technologies are expected to play a central role. To strengthen the CAMRAS program model, it was essential to study the approaches and industrial policies adopted by China, the EU’s Fraunhofer model, the UK, and Japan in developing large-scale manufacturing capabilities.

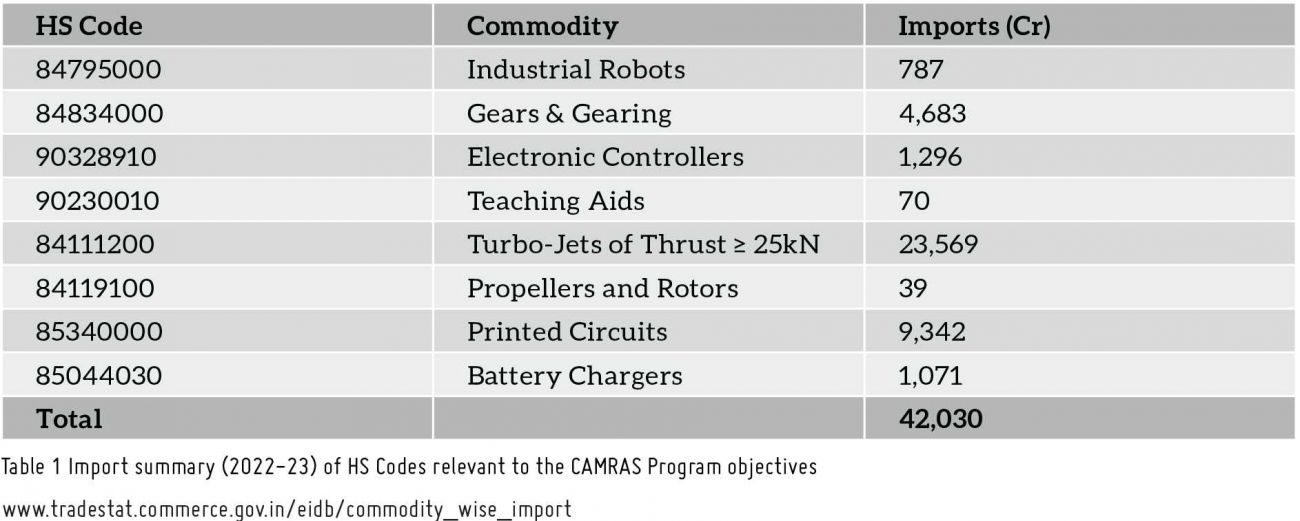

A key observation across these countries is the scale of investment, long-term continuity, and strategic focus on their initiatives. India faced challenges on all three fronts that led to the development of an innovation accelerator model in 2022 that provided agility and better outcomes while requiring reduced investment. Through the CAMRAS program, the focus was placed on technologies and products in robotics, autonomous systems, and drones. Table 1 presents the import summary of products/components when the CAMRAS program was conceptualized in May 2022. It is evident from Table 2 that the focus was not just to create autonomous systems, but also to establish supply chain ecosystems to indigenize them. The program aimed to generate momentum and funding to scale production and achieve global competitiveness.

| Timely flow of funds, asset management, expense management, technology development, budget tracking, cost of goods sold (COGS) management, customer business scaling costs, support models and other policies have a significant impact on the success of the program. |

FIA Ecosystem Model – Case Study of the MHICAMRAS Program

The MHI had conceptualized the Accelerator program in 2022 under its phase-2 scheme of Capital Goods. Thus, the analysis at IISc and MHI converged to initiate the CAMRAS program after a thorough evaluation. The program was convened through another IISc entity focused on AI and robotics technologies named ARTPARK. The aim was to target the creation of new startups with the Project Implementing Organization (PIO) also acting as the Industry Partner (IP) in these areas under the new model and drive the creation of market-ready products and technologies (TRL-7/8) to create the supply chain ecosystem by 2026.

The intention was to create these companies and a replicable model that allowed operational flexibility for speed and IP development with startups in these advanced technology areas (Table 2) and get large industry players to become their customers to scale this model within India at different places.

Given the strict timelines of the CAMRAS program, the maturity of the technology at the start and its complexity, the authors identified key drivers to work on and innovate the FIA model. The objective was to ensure the success of this new CAMRAS program and its startups and create a proof for larger industries, MSMEs and ministries to use this innovation model and make India a sizeable global manufacturing hub. The identified drivers were:

- Leadership talent to initiate these projects with the objective of creating a company during the course of the program and then accelerate its growth after three years.

- An operating model to evolve the project into a company with market-ready products.

- Detailed planning and timelines to guide the progression of technologies from TRL 3–4 to TRL 7–8 in 3 years.

- Focus on innovation and indigenization through patents and develop Indian suppliers for the newer product or components.

- Provide industry-standard infrastructure for product development, certifications, team scaling, prototyping, and manufacturing readiness to attract venture-backed or strategic investments.

- Encourage startups to secure players from the industry and defence sectors as early anchor clients.

- Ensure that startups are able to generate revenue while leveraging each other’s technologies and products to build an internal supply chain for core strategic technologies.

The Ministry of Heavy Industries identified a set of metrics to evaluate accelerator performance under the Capital Goods Scheme Phase II. The CAMRAS program introduced additional metrics to achieve broader objectives—namely, establishing successful and scalable companies through this program. The following metrics were used to measure the CAMRAS program and the success of the FIA model:

- New companies, technologies, and products created

- Patents filed in India

- Degree of innovation and indigenization achieved in technologies, products, and components

- Revenue generated by participating companies against set targets

- Core talent developed within the program, including upskilling of professionals in emerging areas

- Number of Indian suppliers established to support the new product ecosystem

- Investments raised by the companies and their resulting valuations

- Potential for future technology development that positions India ahead of global competitors beyond 2030.

Given the budgetary support from MHI, with no VCs/industry players coming forward to invest at that stage, it was clear that the Exponential growth model will not work for CAMRAS. Consequently, it was decided to implement the FIA model, setting the stage for startups to switch to the Exponential model at a later point.

Risks and Scale Potential of FIA Model

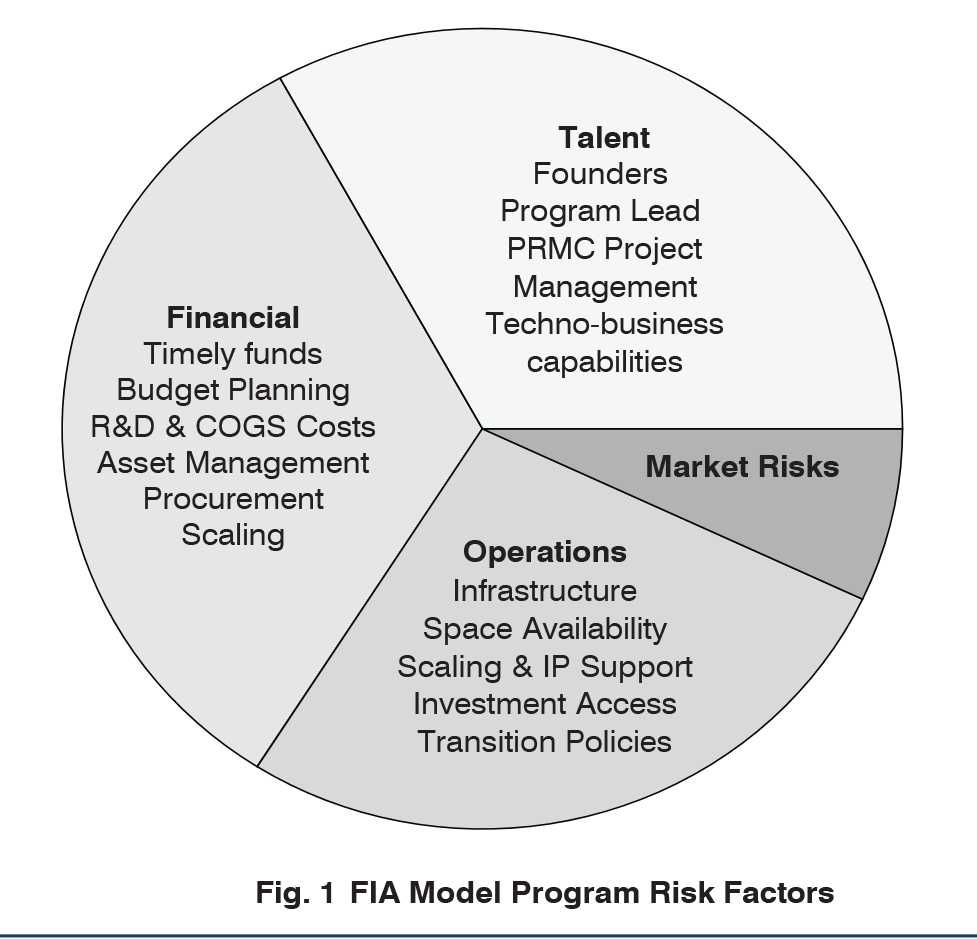

The outcomes demonstrate that the FIA has been successful, though certain areas still offer scope for improvement. Three key risks associated with the model are outlined below (Figure 1).

Talent – It is absolutely important to understand that the success of the program depends on the choice of leaders — Entrepreneurs in Residence (EIR), core startup teams, PIO/ministry leadership, and the overall program leader. Their competencies must range from leadership, behavioral and financial management, program and project management, business management, industry relations, investment/VC relations, team management, and technology integration. This enables culture building within startup teams. They must develop these competencies as part of their journey. However, this is not an easy task, and various environmental operating factors impact that. This risk handling has been rated as 8.75/10 for the CAMRAS program.

Financial – Timely flow of funds, asset management, expense management, technology development, budget tracking, cost of goods sold (COGS) management, customer business scaling costs, support models and other policies have a significant impact on the success of the program. For CAMRAS, this risk handling can be rated as 9/10 for the MHI due to timely cashflow support, and the parent institution (PIO) as 7.5/10, given its dependence on other support funds with their cashflow related challenges.

Operating Policies and Freedom – Support for scaling manufacturing setups, developing common infrastructure, support for startup transitions, plans to raise investments and ensure business sustainability are all critical factors for program success. Additional considerations include space availability, allocation processes, transition mechanisms from EIRs to startup teams, and shared financial, HR, operational, and patent support systems managed by the PIO. Given the evolving nature of the PIO, its institutional dynamics, and the challenge of attracting private and industry investments within short timelines while refining its own operating model, this risk management aspect has been rated at 7/10.

The white paper can be accessed here: www.imtma.in/images/media_coverage/2025/MHI_Paper_LateX_v7.pdf

|

DR ANURAG SRIVASTAVA |

|

SHRI VIJAY MITTAL |

|

SHRI VIKAS DOGRA |

Facebook

Facebook.png) Twitter

Twitter Linkedin

Linkedin Subscribe

Subscribe